Local User Accounts

By default, Ubuntu creates a primary user account during installation, which is a local account with administrative privileges. This account is used to perform administrative tasks on the system, such as installing software or configuring system settings. Also, System accounts are created during the installation or when specific system services are installed. These accounts are given specific privileges and permissions that allow them to perform their designated tasks, such as accessing system files or running system services.

In this post we will look at ways that adversaries can create, reactivate and re-purpose local user accounts and also discuss auditd rules that can be used to detect such activity.

MITRE ATT&CK technique, T1078.003 - Valid Accounts: Local Accounts

Adversaries may obtain and abuse credentials of a local account as a means of gaining Initial Access, Persistence, Privilege Escalation, or Defense Evasion. Local accounts are those configured by an organization for use by users, remote support, services, or for administration on a single system or service.

Local Accounts may also be abused to elevate privileges and harvest credentials through OS Credential Dumping. Password reuse may allow the abuse of local accounts across a set of machines on a network for the purposes of Privilege Escalation and Lateral Movement.

Techniques

User accounts

User accounts on Linux (and other operating systems) are to provide a way for individuals to access and use the system while also ensuring that the system resources are properly managed and protected.

1. Create local account (Linux)

An adversary may wish to create an account with admin privileges to work with. In this test we create a “art” user with the password art, switch to art, execute whoami, exit and delete the art user.

useradd --shell /bin/bash --create-home --password $(openssl passwd -1 art) art

usermod -aG sudo art

su art

whoami

exit

userdel -r art

Lock and expire, not delete

There are several reasons why a system administrator might choose to lock and expire a user account rather than deleting it outright. For Data retention requirements, Historical record-keeping or Temporary suspension while the user is away.

Locking and expiring a user account provides a way to preserve data and maintain historical records while preventing unauthorized access to the system. However, it is important for administrators to also ensure that the locked and expired accounts are properly managed and periodically reviewed to ensure that they are still needed and are not posing a security risk.

2. Reactivate a locked/expired account (Linux)

An adversary may reactivate a inactive account in an attempt to appear legitimate.

In this test we create a “art” user with the password art, lock and expire the account, try to su to art and fail, unlock and renew the account, su successfully, then delete the account.

useradd --shell /bin/bash --create-home --password $(openssl passwd -1 art) art

usermod --lock art

usermod --expiredate "1" art

cat /etc/shadow |grep art

# note: the ! before the password means that the password is locked

# art:!$1$VUdH8K8o$2Lzd5/8nKKyDTf7ZEbLCn0:19405:0:99999:7::5113:

passwd --all --status |grep art

# note: the L means the account is locked

# art L 02/17/2023 0 99999 7 -1

su art

# -> Your account has expired; please contact your system administrator.

# -> su: Authentication failure

usermod --unlock art

usermod --expiredate "99999" art

usermod -aG sudo art

usermod --password $(openssl passwd -1 art) art

su art

whoami

exit

userdel -r art

nobody, special user account

The “nobody” user is a special user account that is commonly used in Unix-based operating systems such as Linux. It is used to represent an unprivileged user or process that should not own files or run programs with elevated privileges. The user ID (UID) of the “nobody” user is typically 65534, which is the maximum value for a 16-bit UID. The group ID (GID) is also usually set to 65534. The home directory is usually set to “/nonexistent” and the login shell is set to “/usr/sbin/nologin”. The “/nonexistent” directory is a placeholder directory that does not actually exist on the file system. It is used to indicate that the “nobody” user does not have a valid home directory. The “/usr/sbin/nologin” shell is a special shell that is used to prevent the “nobody” user from logging into the system.

The “nobody” user is often used as the default user for processes that do not require elevated privileges, such as web servers or other network services. By running these processes as the “nobody” user, the potential damage that could be caused by a security breach is limited, as the attacker would not have access to files or programs with elevated privileges. However it is one many system accounts that an adversary could re-purpose in an attempt to appear legitimate and avoid detection, here’s how.

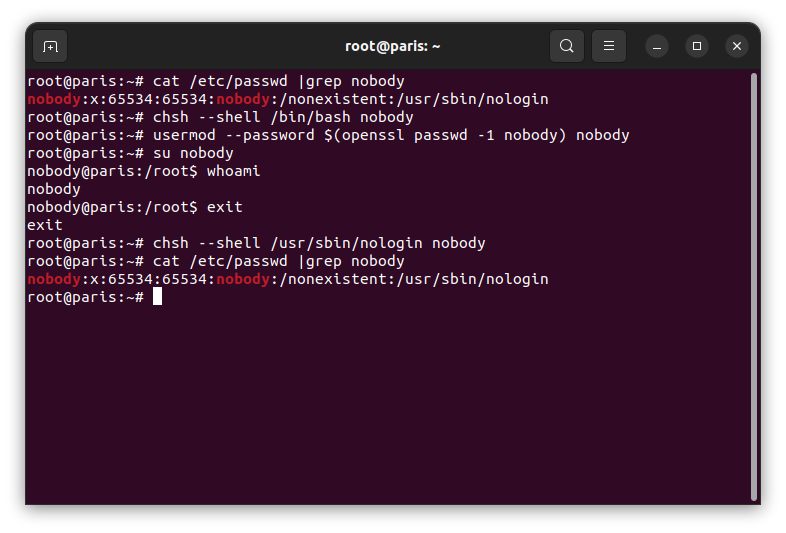

3. Login as nobody (Linux)

An adversary may try to re-purpose a system account to appear legitimate. In this test change the login shell of the nobody account, change its password to nobody, su to nobody, exit, then reset nobody’s shell to /usr/sbin/nologin.

cat /etc/passwd |grep nobody

# -> nobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

cat /etc/shadow |grep art

# -> nobody:*:18667:0:99999:7:::

# note: no password ...

chsh --shell /bin/bash nobody

usermod -aG sudo nobody

usermod --password $(openssl passwd -1 nobody) nobody

su nobody

whoami

exit

chsh --shell /usr/sbin/nologin nobody

cat /etc/passwd |grep nobody

# -> nobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

Detection & logging

Auditd rules

Auditing /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow files can help detect unauthorized changes to user accounts and passwords. These rules will monitor write access to both /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow files and create separate audit records for each file with the corresponding key.

auditctl -w /etc/passwd -p w -k etc-passwd-modification

auditctl -w /etc/shadow -p w -k etc-shadow-modification

Prevention

Preventing the creation or modification of user accounts on Linux systems can help ensure system security and prevent unauthorized access. However, once an adversary gains root privileges and is in a position to undertake any of the above actions, you may have only one option: to remove the ‘useradd’, ‘usermod’, and ‘userdel’ utilities from the system altogether.

Ten points if you got this far, hopefully you found something useful. :-)

Links

- MITRE ATT&CK: https://attack.mitre.org/

- T1078.003 - Valid Accounts: Local Accounts https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1078/003/

- Auditd documentation: https://linux-audit.com/

- Linux Handbook: https://linuxhandbook.com/